The High Victorian train station on what is now the National Mall was virtually empty when the president and his secretary of state walked inside to catch a train north. But on this steamy July day in 1881, the president would not make his train. Instead, James Garfield was shot twice by a disgruntled madman. He would spend the next two months in agony as inept doctors rummaged around his organs looking for the bullet and his insides became infected until he died. For weeks, the nation, the memory of Lincoln’s assassination still fresh, waited. Waiting was all they could do, and that went for Vice President Chester A. Arthur, too. Thanks to the gunman, Charles Guiteau, a shadow hung over a man who was a national afterthought. Upon completing his long fantasized revenge, Guiteau was reported to have joyfully declared, “Arthur will be president now.”

Arthur did become president, and shocked the nation with how seriously he took on reform. But official Washington was in for a more intimate shock. Upon arriving in the capital to assume the presidency, Arthur said of the White House, “I will not live in a house like this.” Instead, he hired the country’s star interior designer, Louis Comfort Tiffany, to transform the White House into an elaborate and over-the-top spectacle you needed to see to believe. There were disco-ball Islamic wall sconces, gold and silver splashed about, and a multicolored giant glass screen that glittered like a dragon’s hoard. Almost all of it, including an object now considered one of the most valuable in White House history, is completely lost.

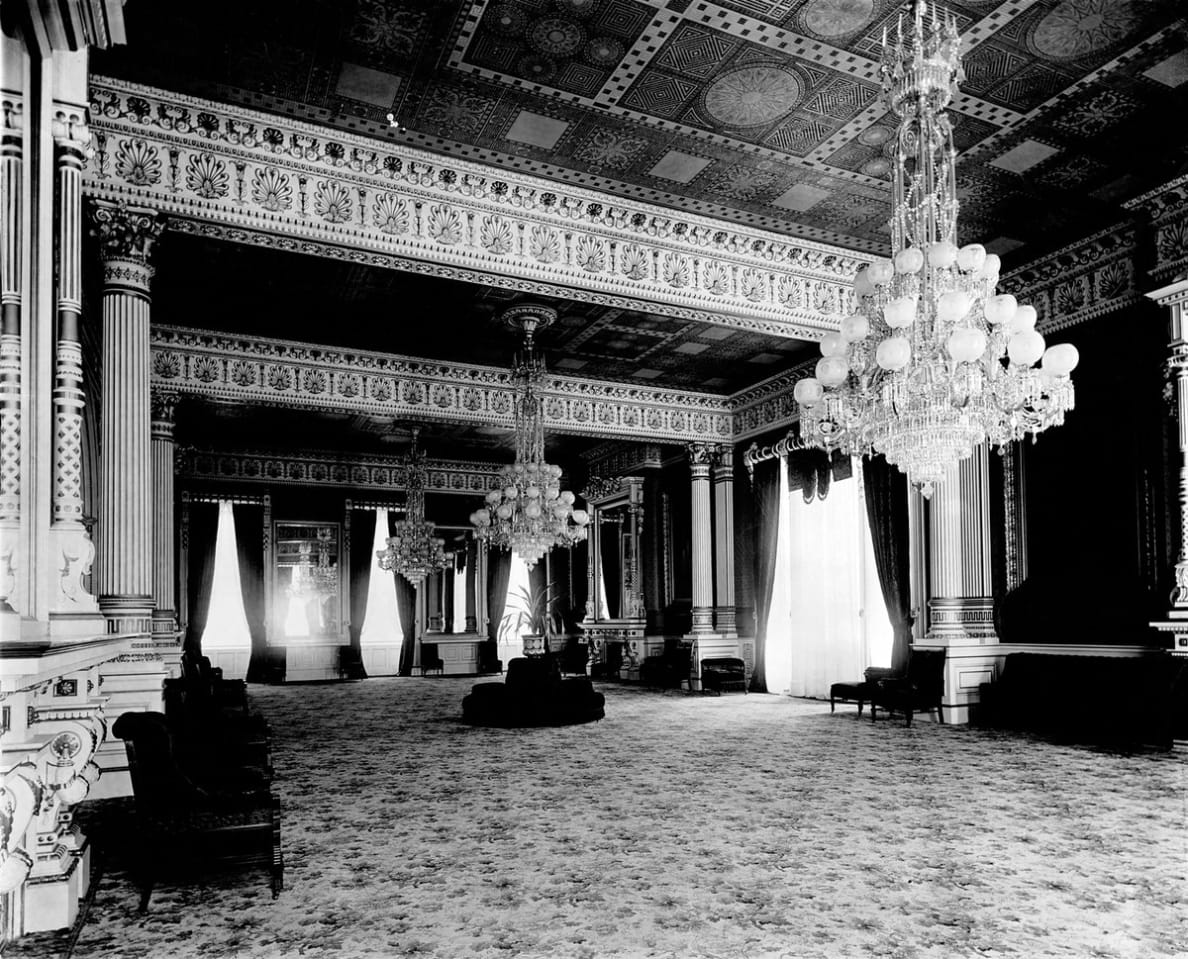

This circa 1889 black and white photograph depicts the East Room of the White House after the Tiffany redecoration.

Library of Congress

In the long list of people who were never meant to be in charge but were put there by fate, Chester A. Arthur was really, truly, completely never supposed to be president. A machine-politics operator who had never been elected to public office, the only thing he was known for was being pushed out as head of the U.S. Custom House in New York when it was engulfed in a corruption scandal. In this era of weak presidents, Arthur was a lieutenant for one of its true powers–U.S. Sen. Roscoe Conkling of New York, who controlled a wing of the Republican Party known as the Stalwarts.

When Conkling and company failed to get former President Ulysses S. Grant the 1880 nomination (for a third term!), dark horse candidate James Garfield was selected, and to bring the party together his team’s second choice was Arthur. Thinking Garfield would lose and damage the brand, Conkling opposed it. But Arthur, clearly more self-aware, had aspirations so low that when offered a job famously described as worth less than “a warm bucket of piss,” he told the vituperative senator, “The office of the vice president is a greater honor than I ever dreamed of obtaining.” The outrage within the party of somebody so tainted by corruption being named vice president was quelled by the reality that the vice president had no power, and it was impossible to imagine Arthur would ever advance beyond it.

But on Sept. 19, 1881, the man who was supposed to be the country’s most forgettable vice president became one of its most forgettable presidents.

Arthur was perhaps our most diva president. He had as many as 80 suits, all made custom by a New York tailor. They came in handy as this man who was born in a log cabin was known to have multiple outfit changes a day and wear a tuxedo to dinner. He worked only a few hours a day, and held parties and dinners until the wee hours of the morning. Arthur was heavy-set and got around D.C. on a leather-trimmed carriage adorned with his coat of arms painted in gilt, lamps of silverplate, gold lace curtains, and lap robe of otter fur lined with green silk. It was pulled by horses draped in blankets with the gold-thread monogram C.A.A. He brought to the capital a French chef, and his New York City townhouse had a sitting room decked out in white and gold. Upset that the elevator he had installed in the White House was too simple, he had it redone in tufted plush.

White House Historical Association

One need only look at his baronial presidential portrait to see that this was the Gilded Age president with all the airs to mirror those of the newly wealthy of New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and San Francisco. Like any good New Yorker with pretensions, he was a customer of Tiffany & Co. and made his way to the Park Avenue Armory, completed in 1880, to see the new Veterans Room designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany (the son of Tiffany’s founder) and his team which included Stanford White, Francis Millet, Candance Wheeler, and Samuel Colman. When Arthur saw the state of the White House—after its decor had been ignored by staid party poopers like Hayes and then partially turned into a hospital for Garfield—he decided a redecoration reflecting the country’s status was required and there was really only one man for the job.

As urban American families in the 19th century accumulated large amounts of wealth, they looked for ways to spend it that would show off their lucre: clothes, jewels, art, and homes. The houses began to be designed by professional architects in a variety of styles rather than by builders in just a handful of aesthetics, and wealthy Americans clamored for interiors that made as much of a statement as the outside. By 1881, interior decoration in America was undergoing a revolution from which it would never return. For decades, the interiors of grand houses had been done up by furniture and cabinet makers, the most prestigious of which was Herter Bros. who designed the interior of the largest house in New York City history, Cornelius Vanderbilt II’s mansion. The craftsmanship was top notch, but the flair and artistic quality was uninspired. And with the advent of easily disseminated photographs and magazines showing how each house was one upping the other, an interior with flair was very much in need.

At the same time, says Jennifer Thalheimer of the Morse Museum (where I first came across images of Tiffany’s White House decor), “there’s a lot of infighting at the National Academy of Design,” and younger artists who no longer had access to the structural support of the academy started “looking for a way to supplement their lives … so they looked to interior design.” The most prominent of these frustrated artists-turned-decorators was Louis Comfort Tiffany.

He had traveled the world and tried his hand at painting and was well on his way to being one of the greatest glassmakers in history. He was a man of “dumbfounding versatility,” according to one critic, a phrase I wish would replace the overused Renaissance Man. Hugh McKean, author of Lost Treasures of Louis Comfort Tiffany, observed that Tiffany hated the phrase “fine art … [his] entire life was a revolt against this precious attitude,” and he was determined to show the lesser arts of design and decorative objects could be truly fine art.

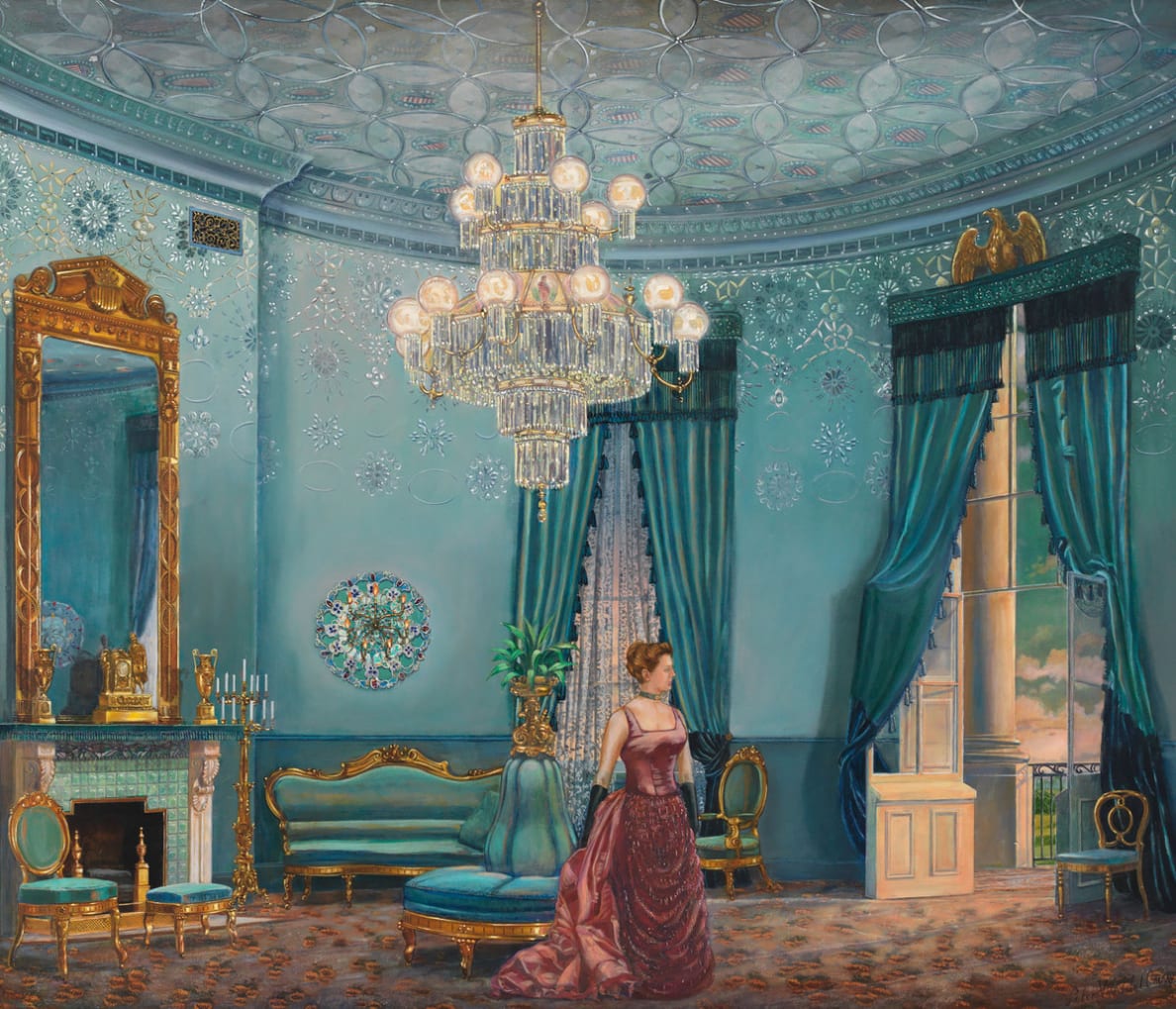

The Blue Room as decorated by Tiffany.

Library of Congress

In 1879, after “he came to accept his shortcomings as a painter,” as Philippe Garner snidely noted, he launched a decorating company with the painter Samuel Colman and textile designer Candace Wheeler called Louis C. Tiffany and Associated Artists.

Associated Artists quickly became the designers, a status reflected in how many of the homes in that era’s design bible, Artistic Houses, were theirs. Tiffany was an “artistic decorator, not a regular interior decorator,” explains Thalheimer. “He’s going to put art in your home and surround you with beauty and new ideas and the most cutting edge stuff.” Today, there are only two places where you can experience their work largely intact: Mark Twain’s house in Connecticut and the aforementioned Veterans Room in the Park Avenue Armory. The Veterans Room is an orgy of materials and patterns so complex and detailed your eyes cannot rest. Intricately carved wood screens, a fireplace of blazing Silk Road blue, and elaborate stencil work cover every inch. At the southern end of the armory’s hall one finds a room done entirely by Herter Bros., which is lovely in a wood-paneled clubhouse sort of way but wilts in comparison to the “Art for Art’s Sake” tour de force that is Tiffany’s Veterans Room.

The Veterans Room also matters because Chester Arthur is believed to have visited it before making his decision to enlist Tiffany to redo the White House.

While hard to imagine now—indeed, to even acknowledge now that the People’s House is anything other than perfect is politically dangerous for presidents—the White House’s occupants often thought it was a dump with little to no privacy, filled with rats, poorly furnished, and in danger of collapsing. Mrs. Garfield had been appropriated some money for a redecoration, but it was never completed, which left the house in disarray with unfinished pipes laying around, half-done carpentry and paint jobs, and naked windows. When Arthur assumed the presidency he stayed at the house of his friend Sen. John P. Jones of Nevada rather than the White House and used the Garfield sums to finish the decoration they started. But he began visiting daily to inspect the space with the head of the government engineering office.

The report put together from these inspections was scandalous. Servants quarters were so dank they caused sickness, and the kitchen’s chipping whitewash often fell into pots of food. The White House was quite literally sitting on a pile of shit as the pipes for several of the toilets had decayed so the waste ended up under the basement. The State Dining Room of all places still had chamber pots. The report was submitted to Congress, and the Senate actually passed a bill for a few hundred thousand dollars for the White House to be torn down, replaced with a replica for executive offices, and a new residence built to its south. But that plan died, and Arthur realized if he was to have a grand home he’d have to work with the existing building.

In May of 1882, Louis Comfort Tiffany, then 34, met with Arthur at the White House and agreed to redo the East Room, Red Room, Blue Room, the State Dining Room, and the Transverse Hall. The Green Room would be left untouched. For this herculean task which needed to be completed in six months, Tiffany would be paid a flat fee of $15,000, which was three quarters what he made for the single room at the Armory. But as historian Wilson H. Faude explained, “few commissions as important as the White House existed,” and “any changes to its interiors would be noted and imitated by other decorators and clients.”

To ready the White House for Tiffany’s vision, Arthur went room by room deciding which furnishings would stay and which would go. A total of 24 wagons of what would be now priceless furnishings went out for auction, including Andrew Jackson’s stand-up writing desk. (Apparently none other than former President Rutherford B. Hayes was monitoring the auction lists and snatched up the mahogany State Dining Room carving tables.)

Tiffany brought a crew from New York that was willing to work day and night with only the president allowed to visit. Plenty of objects remained, however, and Tiffany had to incorporate or work around them. The thematic room colors also had to remain, and so while blue, and light blue in particular, were unpopular colors in 1882, “the Blue Room was suffered to remain a blue room,” sneered Artistic Houses. That undersells what Tiffany got away with—something that is hard to fathom even with photographic evidence and colored renderings.

This 2007 oil painting captures First Lady Frances Folsom Cleveland standing in the middle of the room looking through opened windows to the South Portico. Louis Comfort Tiffany’s 1882 redesign and redecoration of the room is represented in this painting with rich, bold colors.

Peter Waddell for the White House Historical Association

The Blue Room is where the president received the credentials of foreign diplomats and greeted guests. Oval in shape, Tiffany found it an ideal form to play off the idea of a robin’s egg. If you were to visit in the daytime, which few did, it would have seemed a sort of sickly green, but at night, when most events were held under gaslight, it was a brilliant blue. (As a protege of the painter George Inness, Tiffany was notable for his precision with the effects of different types of light.)

Tiffany was a “dye-in-the-wool Republican,” Robert Koch writes in Louis C. Tiffany: Rebel in Glass, “and proud of having decorated the White House for President Chester A Arthur.” So on the ceiling of the Blue Room he went full nationalist. A doily-like allover pattern with white and silver interlocking ovals covered the ceiling, and at the center of each oval was the red, white, and blue stars and stripes shield of the White House. Below the ceiling was an 8-foot-wide frieze of hand-embossed silver and gray patterns that resembled snowflakes. The color on the wall gradually darkened from the silvery frieze to robin’s egg blue to a dark blue wainscoting. The curtains were also dyed to have three separate bands of color to match the walls. On the existing fireplace Tiffany added squares of opalescent glass.

But the real shocker was hanging on the wall: four circular sconces influenced by Islamic design. Each was a 3-foot wide rosette of hundreds of pieces of mirrored and colored glass which provided a backdrop for seven unshaded gas jets the arms of which were dripping with pendants of iridescent glass. The sconces, writes Koch, “must have beamed like disco balls.” One journalist remarked in his coverage that these balls were “wrinkled in order to catch light from many angles.” Thus was a stately and dour room transformed into something scintillating and fun, and so overwhelming that you’d (hopefully) not notice the gilt Louis XV revival furniture and the circular divan.

If the Blue Room was a sparkling showpiece, it was the Red Room where Tiffany really flexed his colorist muscle. It’s a space in which the designer seems to say, “Oh, you want red? I’ll give you red!”

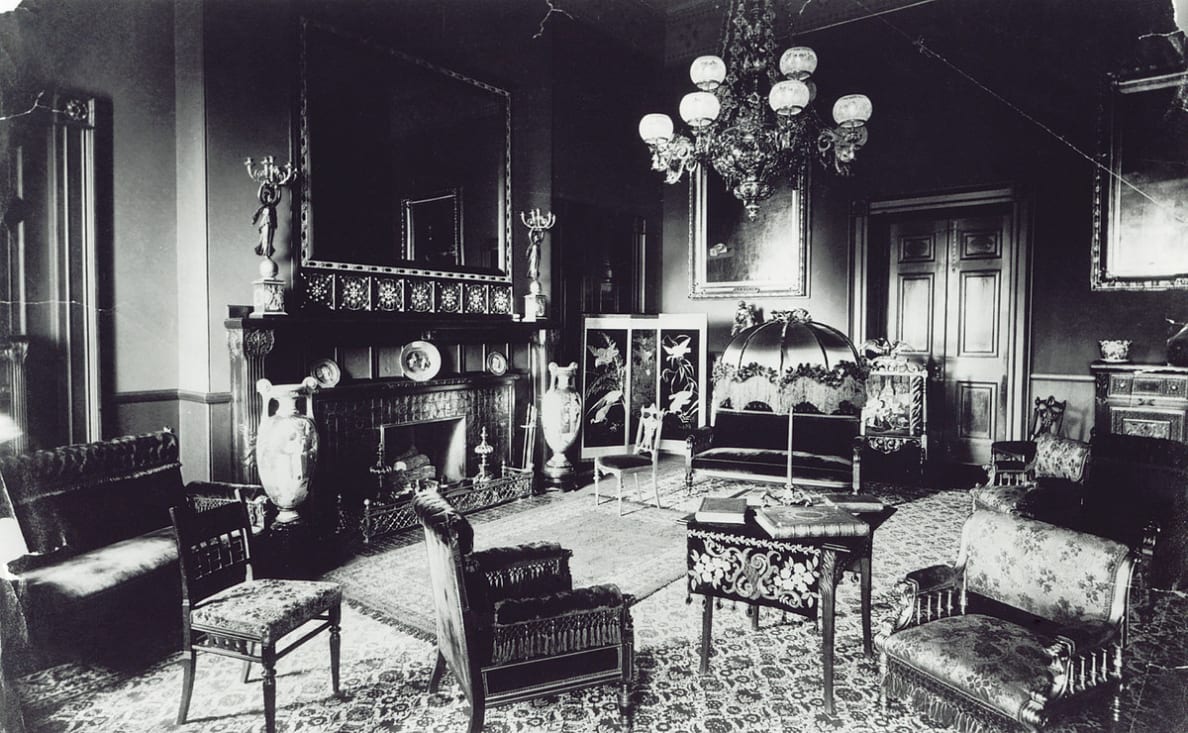

This painting by Peter Waddell depicts the Red Room in 1883 during the Chester A. Arthur administration, with President Arthur’s sisters, Mary and Malvine.

Peter Waddell for the White House Historical Association

“When first I had a chance to travel in the Near East and to paint where the people and the buildings are also clad in beautiful hues, the preeminence of color in the world was brought forcibly to my attention,” Tiffany would later say. “I returned to New York wondering why we made so little use of our eyes, why we refrained so obstinately from taking advantage of color in our architecture and our clothing when Nature indicates its mastership.”

For the Red Room, Tiffany continued with the idea of color gradation. The walls were painted a sumptuous Pompeiian red that verged on claret while the wainscoting was a darker almost currant color. The frieze was verging on pink and, in the words of White House historian William Seale, covered in an abstraction of stars and stripes. The wood trim was also covered in a dark red paint but rubbed until it was glossy.

The Tiffany furnishings and Red Room decor, including the copper and silver ceiling in a star motif and the Herter Brothers armchairs, are including in this composition.

Library of Congress

Already drowning in red, Tiffany added two more elements that would have left one gobsmacked. The first was the fireplace, and for that he had the pre-existing white marble one ripped out and replaced with one of cherry designed by Art Nouveau master Edward Colonna. Around the opening was a mosaic of glass tiles colored amber and red to enhance the flickering flames within. Around those were panels of Japanese leather tinted red set into the cherry. Above the actual mantel but below the existing mirror was another glass mosaic, this one with embedded glass gems. And the original gilt mirror was framed in red plush upholstery.

The ceiling was the other scene steal, as Tiffany had it painted with circles of bronze and copper stars on a gold background, varnished such that any bit of light was reflected. Most of the furnishings were pieces that Tiffany repurposed, whether candlesticks from President James Monroe’s administration, a silk screen gifted by Austria to Grant, Lincoln’s office clock, or Sevres vases from France peculiarly decorated with scenes of the conviction and sentencing of Charlotte Corday (assassin of Jean-Paul Marat). As for the piano found there, one critic wrote: “For its presence I believe the decorators are not responsible.”

Tiffany wasn’t some whirling decorating dervish throwing sparkle everywhere. In the State Dining Room he understood that there would normally be lots of flowers, fancy dresses, and a shiny dining service so he kept things simple. The walls were painted yellow (fawn, to be specific) and a series of hammered silver reflectors were added to gas brackets to lighten the space. The ceiling and frieze were painted primrose and lemon with rosettes.

The largest of the state rooms is the East Room, and here Tiffany was also restrained as the walls had recently been redone in white and gold. He brought in new objects like Turkish chairs and circular divans as well as a sienna-colored Axminster rug. On the ceiling, William Seale writes, Tiffany decorated it with squares colored rust, gold, and brown to resemble old wallpaper and match the amber window hangings; Artistic Houses described it at the time as a “small mosaic pattern, in silver-leaf, which easily receives the reflection of the carpet.”

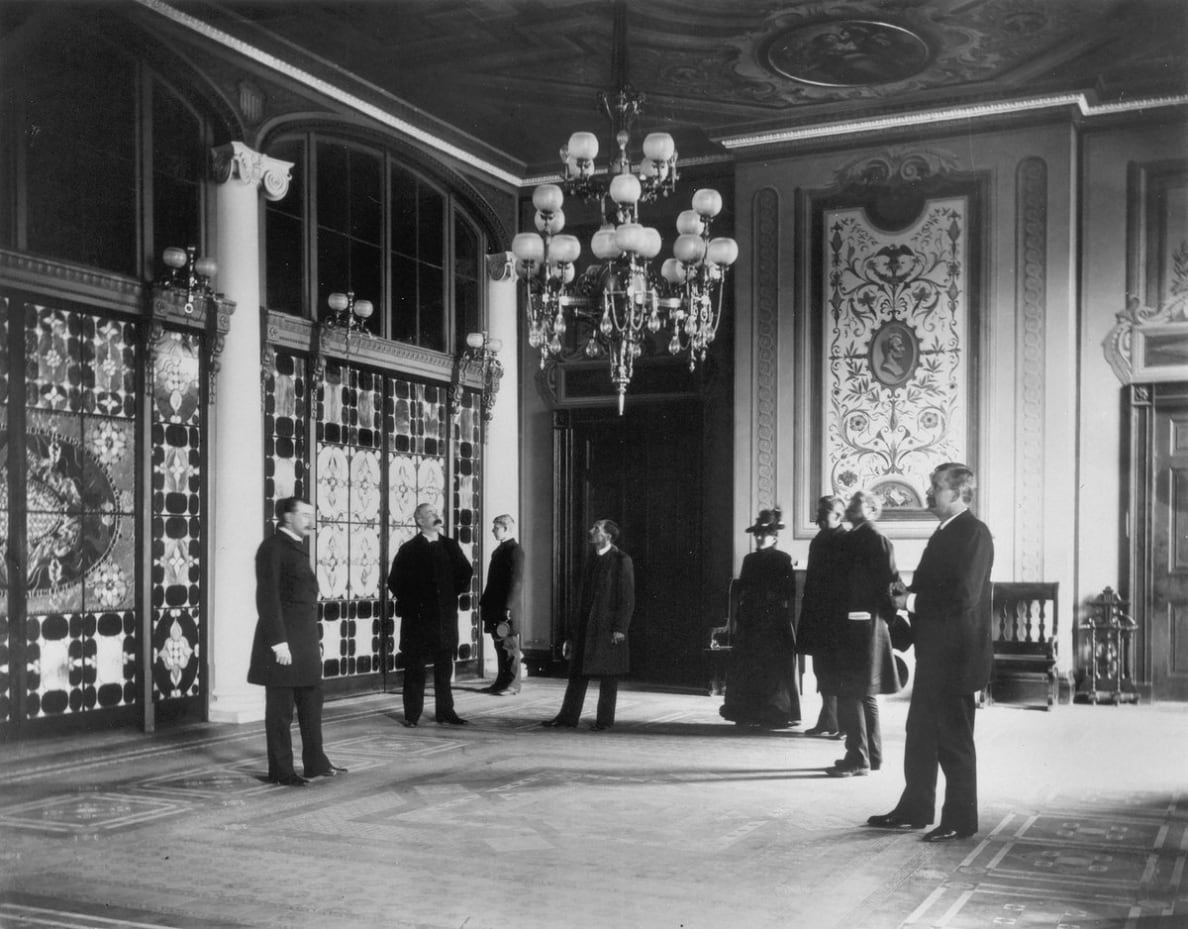

In 1882 Chester A. Arthur commissioned the interior designs and decorative arts of Louis Comfort Tiffany to make the Entrance Hall more welcoming.

White House Historical Association

While Tiffany’s designs for the rooms of the White House were a spectacle, one addition was undoubtedly the most famous: his glass screen separating the entrance hall from the transverse hall which ran along the Red, Blue, and Green Rooms and connected the East Room with the staircase. The screen, theoretically, gave the president and family some privacy from guests in the entrance. In the White House, the existing screen of smoked glass had been put in place in the 1850s, and before that it was a screen (unsexily named the “draft eliminator”) installed by White House architect James Hoban. Tiffany was already a prolific glassmaker and his kaleidoscopic leaded glass curtain was immediately seen as a masterpiece. A variety of shades of red, white, and blue were splashed between the four ionic columns. WIth walls painted a cream color and a ceiling “stenciled with a silvery network like a spiderweb,” writes William Seale, the “stained glass made the long hall continually iridescent.” It had an effect, Century Magazine declared, that was “rich and gorgeous.” Looking through photos of Tiffany’s theatrical White House designs, the screen is the sole element that looks like it truly belongs with its surroundings. It was especially spectacular during state dinners, as tables even through the McKinley era would be set up just underneath its gem-like array.

The glass screen was removed and auctioned off during the Roosevelt renovation, and reinstalled in a Maryland hotel. The surviving glass was destroyed in a fire in 1923. Note the electric light bulbs along the bottom of chandelier. The ornate wall decorations were designed by upholsterer Edgar Yergason.

Peter Waddell for the White House Historical Association

For months, the only outside person who had been able to see the work was Arthur, but on Dec. 19, 1882, a press preview was held. The reaction was mixed. One newspaper crowed, “No longer is the White House simply the home of a Republican president. Lo, it is the temple of high art.”

“Tiffany, a romantic,” another said, “had added whimsy, sparkle and surprise to a stately classic building.” One reporter, William Seale writes, said the Red Room was “overpowering” in “richness and antiquity.” Of the screen, most were effusive, with one declaring, “It is so much better than any glass which can be produced in Europe today that the typical American should point to it as one of our surest titles to respect when enumerating them for the benefit of the typical foreigner in Washington.”

Illustration of a January 17, 1900 State Dinner hosted by President William McKinley and First Lady Ida Saxton McKinley in the White House Cross Hall. The famous Tiffany glass screen is seen in the background.

White House Historical Association

Tiffany reportedly saved all the clippings, good and bad. One negative review he would likely have held onto was in The World: “[Tiffany’s decorations] are not ideally good by any means, not ‘monumental,’ not ‘high art’ at all. In spite of all the abuse that has been heaped upon it, the White House is a fine old mansion, extremely well-planned for its purpose—except as to staircases—and being capable of being made into a beautiful building. It ought to be decorated someday from end-to-end in a truly good style with the best products of the chisel and the brush.”

Perhaps the most cutting was in Artistic Houses, where the author damned by faint praise: “The beauty and artistic value of the Messr. Tiffany’s decorations are best appreciated by those guests who know how the White House used to look.”

As far as Washington society went, the rooms were by and large a hit. Even Mrs. Blaine, the trenchant wife of former Secretary of State and perpetual presidential aspirant James Blaine was forced to concede. What she referred to as “the White House taint” was gone and instead it showed “the latest style and an abandon in expense and care.”

But if Tiffany’s rise as a designer was rocket-like, his fall was even faster. Just a few years after the White House was completed, the heavy, busy, and crowded “Victorian clutter” that he enacted was out. While Louis Comfort Tiffany’s glass and decorative art are considered extremely valuable today, in the years before his death they were passé. Just 7 years after he finished his White House overhaul, First Lady Caroline Harrison was undoing some of his work and planning to build an entirely new residence.

While her plan was torpedoed by a vengeful congressman, it resurfaced at the turn of the century with proposals for an expansion or entirely new residence. “No little plans,” was Washington’s mantra in this period, an attitude best captured by palatial proposals for the vice president’s residence and the National Mall). After yet another assassination, this time President William McKinley, another accidental president dramatically reshaped the White House. Teddy Roosevelt and First Lady Edith turned to the senior partner in the world’s biggest architectural firm, Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White. His restoration would be merciless to Tiffany’s work. When it came to the iconic glass screen, McKim famously sneered, “I would suggest dynamite.”

Beginning in 1902, McKim removed nearly all traces of Tiffany’s work and sold off the furniture. When he was tasked with the job, McKim proposed to “take [the White House] down stone by stone … and rebuild it; and not another architect in the country can make a finer or more appropriate residence for the President of the United States.” He turned the White House into the paragon of Colonial American decor we associate it with today, but with an elegance on par with European palaces. As to those who lamented the lost pizzazz of Tiffany, The New York Times went on the attack, declaring the critics were upset by “the simplicity and moderation, the chastity and good taste, which belong to the restoration of a Colonial Mansion” and just chafing at the “absence of that ‘palatial magnificence’ which is to be found in so many hotels and so many steamboats and so many barroms.”

But in a morality play of what goes around comes around, McKim’s overhaul would also fail to stand the test of time. Yet another accidental president, this time Harry S. Truman after Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s death in 1945, would redo the White House. This time it was a full gut job down to just its shell. A decade later, First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy’s version of Colonial design (a “restoration” not redesign, she would emphasize) would ultimately win out.

As for that Tiffany glass screen? It reportedly ended up in a Baltimore hotel and disappeared for good when the hotel burned down in 1923.